Having lived in the Western United States my entire life, I am accustomed to hearing the larger than life myths that accompany this region. Myths are hard to change. Some of the most famous myths have long been embedded in the overall picture Americans have of ourselves. I would like to affirm some myths and deconstruct others regarding The American West and the Indigenous People who live there.

The boundary of the Western United States has moved westward several times since it was first identified. To an Eighteenth Century Virginian, such as Thomas Jefferson, the West was a wilderness populated by hostile Indigenous tribes. The West was also viewed as an open region, populated by "backward savages." The US governmental view was that the Indigenous tribes were not "using" the land beyond the Cumberland Gap, one of the West's first identified mountain passes. Indigenous lands were invaded by White settlers who turned old growth forests into farmland. The war with Western Indigenous tribes had moved further West. This type of invasion was to be repeated with westward expansion as a result throughout the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries.

The notion was that these "uncivilized savages" should not retain their lands, and that "civilized" European-Americans were needed to occupy Indigenous lands. These "pioneers," as they were called, were supported by the US government financially, militarily, and sociologically. The lands west of Cumberland Gap were assumed to be open for agricultural development and the pioneers were told that they were expected to use such land in a manner as defined by the new USA. The "pioneers" (e.g. invaders) were lionized as heroes. A parade of "Americans" were honored in literature designed to justify the displacement of Indigenous tribes and the continued enslavement of African-Americans.

The "Unconquered West" was to become the target of seekers of gold, arable land, and a national attitude that was labeled "Manifest Destiny."

The philosophy called Manifest Destiny was one of the pillars of the ideological superstructure used to expand European-American control over the North American continent. That the US government supported Westward expansion was never seriously questioned. Although Manifest Destiny did not enter the American Mythical nomenclature until the Mid Nineteenth Century, the assumption of European-American entitlement to all of North (and South) American lands was embedded in European-American public discourse. This was because "savages" did not make use of their lands in a manner acceptable to the USA, nor did those Indigenous peoples have a concept of land ownership in their traditional beliefs. The God of Abraham, Jesus, and The Prophet was also the European-American God who was personalized by the Torah, Bible, and Quran. Cultural Imperialism became the policy of the US government with respect to Westward Expansion.

The oral traditions of Indigenous tribes in the time prior to and during European-American hegemony westward were as varied as the tribes themselves. Each tribe had a language that may have been similar to other tribes' languages, but was different enough to require bilingual interpreters or sign language communication. There were and are agreements between various tribes that spanned centuries. The Iriquois Confederation of Five Civilized Tribes predated European-American presence by a century. This cooperative agreement, among many others, was evidence that contradicted the second Western American Myth...the "Noble Savage."

The Noble Savage became a primary archetype strengthened by authors like James Fenimore Cooper. There has been a long disagreement among researchers in anthropology as to whether non European-American peoples were similar to or different from Europeans prior to first contact with European-American civilizations.

The Noble Savage myth dates from the Seventeenth Century, and emerged from Romanticism. That the idea of a Noble Savage existed did not stop the US government from promulgating the idea that Indigenous tribes needed to be assimilated into European-American culture with their own beliefs to be eradicated.

Suffice to say that a tribe of Indigenous people, if invaded by European-American culture, will strive to keep secret the beliefs that are most precious to their culture. Perhaps it was this self-preservational dynamic of Indigenous tribes' spiritual, family, cultural, governing, and language structure and beliefs throughout the world that led European-Americans to become determined to erase Indigenous cultures with the purpose of assimilation of such peoples into European-American culture. This process was fairly similar worldwide through the destruction of the very foundations of Indigenous culture...spiritual beliefs, extended clan family structure, tribal decision-making, and most importantly, their native language.

The systematic process of Indigenous Cultural destruction was justified by another Western Myth, the Superiority of European-American Culture over Indigenous Cultures. The arrogant belief that European-American cultures were the key to bringing the Indigenous tribes into what came to be called "The Melting Pot" reflected the Cultural Imperialism of the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth centuries of the Americans of European-American descent.

Progress became intertwined with the Protestant Ethic in the Nineteenth Century, and pursuit of wealth became interwoven with rapid advancements in technology. As improvements in agricultural technology, communication, transportation, and manufacturing emerged, the ease of living in each phase of the New West improved. The Indigenous tribes of North America were gradually stripped of their culture, sources of sustenance, hunting and fishing land, and health. A combination of gradual incursion, curtailment of the various tribes' ability to migrate with the seasons, phony promises made in treaties not worth the paper they were signed on, and harassment leading to further genocide stripped the tribes of the very characteristics and customs that defined them in how they saw themselves and how other tribes saw them.

During the Presidency of Andrew Jackson,the Southeastern regional US Indigenous tribes were ordered to be relocated to the land beyond the Louisiana Purchase to enable the expansion of agriculture and slavery into those tribes' lands. Although the Trail of Tears is the most famous example of President Andrew Jackson's cruel and imperialistic ejection of tribes from their homelands, other tribes experienced similar relocation. The purpose of creation of Indian Territory was to ostensibly reserve that land for Indigenous peoples, but the reality was that fortune seekers, farmers, and riff raff invaded Indian Territory and sabotaged the intended setting aside of land for tribal settlements. This behavior was pervasive throughout the Nineteenth Century.

In the first decade of the Nineteenth Century, Napoléon sold France's Louisiana lands to Thomas Jefferson's United States, leading to the invasion of Louisiana by Lewis and Clark. Their exploration was first contact between the US Government and Missouri and Columbia River drainage area Indigenous Tribes. The tribes that the Lewis and Clark Expedition encountered were generally receptive with a few exceptions. The rivers that flowed into the Missouri and Columbia Rivers were mapped, detailed notation and drawings were recorded, and flora and fauna were carefully described.

The US Army's use of weapons far advanced over those of Indigenous tribes made contact with US troops fatal for too many Indigenous men, women and children to count. The transcontinental railroad was built through hunting grounds. Various mercantile trails and cattle trails crisscrossed what was the edge of the American West. In less than 100 years the Americans had evicted the Southern US tribes, decimated the Northeastern and also the tribes from what is now called the American Midwest. The bison, now America's National Animal, was the source of nearly every tool or food that Northern Plains tribes used. Hundreds of treaties were signed and then broken by US Army officers and troops. Ironically, it was the Indigenous people who were labeled as dishonest.

Cultural Imperialism shoved tribes who were hunters and constantly moving from place to place into lands believed to be useless for American citizens. Labeled as reservations, the tribes were ordered to learn to be farmers on land unfit for growing crops. Tribes were relegated to eating spoiled meat and other food which was unfit for Caucasian consumption. Alcohol was provided to Indigenous people who had never been exposed to it. Rampant diseases, such as smallpox and measles and drinking were ignored by people paid to assist the tribes, often as government agents. Sacred lands, such as the Paha Sapa (Black Hills) were stolen and traditional spirituality ignored or discouraged. As the Nineteenth Century ended, Indigenous people in the USA numbered 250,000. This was down from an estimated 20 million people in the time of first contact with European-American civilizations. Several tribes were "delisted" from US Governmental Tribal lists. This meant that these tribes no longer were even eligible for reservations, medicine, and other life sustaining elements. Other tribes simply died out. The saga of Ishi, a member of a California tribe, the Yahi, poignantly documented his last years as the sole surviving member, residing in a museum as a living exhibit in San Francisco. That Ishi became the last member of the Yahi Clan of the Yana Tribe of California reflects the chaos and danger that Indigenous people faced when having first contact with Caucasians. Later in this article, the history of the State of California will be examined through use of prior scholarly research. See illustrations below:

The annexation of Texas in 1845 into the United States led to systematic military engagement with Indigenous tribes such as the Comanche. Other tribes were also driven from their traditional lands even more rapidly than the Comanche. The demise of the bison from the Southern Plains occurred more rapidly than in the Dakotas, Wyoming, Nebraska, and Montana. The decline of the Southern Plains tribes led to all of their former territories being changed into large ranches or subsistence farming. Although the US government supported this type of farming through the Homestead Act, the lower precipitation and droughts caused hundreds of thousands of square miles becoming unusable and essentially dead. Acreage in such regions remain ruined with little hope for restoration of the tall grass prairies before invaders took the land and ruined it.

Northwestern tribes were either moved or placed on lands that homesteaders could not use. The Apsalooke, known as the Crow tribe, lost their mountain lands to mining and tourism. The Arapahoe and Shoshone tribes were moved from the mountains to a reservation with little useful farming and ranching land. The Utes were moved from their homes in the mountains of Colorado and Utah to two small reservations in Colorado's southwestern corner. These mountain tribes were relocated from their homelands to allow mining and ranching interests access to billions of dollars worth of various minerals, oil shale, and ranches. Thus, royalties for these minerals were paid to the US and State Governments instead of the tribes. In several different periods of time, the US Government looked the other way when oil companies failed to pay royalties to various tribes. That trend was challenged by several tribes, and they maintained that the US government did not exercise due diligence in monitoring output of minerals and oil from the Western US reservations. The tribes' challenge was upheld, and either the US Government or the dishonest companies had to pay tribes their lost revenue.

Tribes in the arid Southwest were generally kept in their traditional lands. Pueblos were protected by their history of being deeded by the Spanish Kinghe famous s through land grants, which were honored by treaty after the Mexican War. The Navajo (Di'neh) were settled on a 25,000 square mile reservation in New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah. This happened after a large portion of the tribe endured the Long Walk from their lands to Fort Sumner, New Mexico. The famous frontiersman Kit Carson along with the US Army conducted a slash and burn campaign against the Navajo, marched them some 400 miles in freezing weather, and then the tribe was told to learn how to farm on the arid semi-desert of New Mexico's Llano Estacado. Some 3000 Navajo died there due to starvation, US Army neglect, and diseases that rampages through the tribe.

the United States as a whole was outraged. Senior Army staff, as ordered by President Grant intensified the "Indian War" against tribes that had not submitted to stay on a reservation. From Washington DC downward, the free tribes, the Lakota, Apaches, Northern Cheyenne, and others faced a search and destroy mission comparable to hunting down ISIS in this time. The remaining free Indigenous tribes kept their way of life for as long as they could.

Important leaders such as President Grant appointed several seasoned leaders, most notably General Sheridan, whose battle tactics were important in the US Civil War. Treaties the United States Government initiated had been broken repeatedly by the United States. The Smithsonian has identified 503 broken treaties with various tribes from 1778 to the present day. This list of broken treaties comes from the National Archive and may be viewed in Wikipedia. This list of broken treaties may be found below:

Treaty-making between various Native American governments and the United States officially concluded on March 3, 1871 with the passing of the United States Code Title 25, Chapter 3, Subchapter 1, Section 71 (25 U.S.C. § 71). Pre-existing treaties were grandfathered, and further agreements were made under domestic law.

In California,. Indigenous tribes suffered even worse than elsewhere in North America. The heavy hand of the Spanish conquerors of what was then Mexico, forced a number of tribes to live near the chain of missions established by Junipero Serra. Though Father Serra was a cut above average colonial missionaries, the fact remains that many of the tribes in California died out or lost their traditional identity under the Spanish. The purpose of the mission system was to gather the Indigenous people in regional groups nearby each mission, and this began when the missions were being constructed, as that was accomplished using Indigenous tribal members. The treatment of Indigenous people by the Spanish was as a slave to master relationship. The priests in the Catholic Missions had harsh penalties for tribes or members who did not accept hard labor. Like many other Spanish Colonial sites, the harsh treatment of Indigenous people went unreported to the Spanish Crown. As happened in Spanish New Mexico, the tribes revolted. They were harshly deprived of their traditional spirituality, and had to keep it hidden from the Spanish to preserve its integrity. The Mexican successors to the Spanish were not as destructive as the Spanish, but did secularize the Missions, and the large ranchos the wealthy land holders built were maintained by Indigenous labor. When the Americans came to California after the Mexican War, the sheer volume of non-Indigenous people meant that many sites where the California tribes did not have the wherewithal to engage the occupiers in battle. There were 310,000 Indigenous people in California in 1769 as tabulated by the Spanish, By 1840, the number had gone down to 100,000, with scarlet fever, small pox, and pneumonia killing huge numbers of Indigenous people, and the number of tribes was severely reduced. During 1850-1860, in American occupation after the Mexican War, the California Legislature adopted laws which were legally set up to essentially treat the Indigenous people as proto-slaves.

In 1850, An Act for the Government and Protection of Indians was enacted by the first session of the California Legislature. This law set the tone for Indian-White relations to come.

The act provided for the following:

This law was widely abused with regard to the use of Indians as laborers, though it did allow Indians to reside on private land. The use of this law to sentence Indigenous People to hard labor was a form of slavery, because Indigenous offenders did not have any other options to choose from.vDuring 1851 and 1852, the California Legislature authorized payment of $1,100,000 for the "supression of Indian hostilities. Again, in 1857, the Legislature issued bonds for $410,000 for the same purpose." (Heizer, 1978:108) While theoretically attempting to resolve White-Indian conflicts, these payments only encouraged Whites to form volunteer companies and try to eliminate all the Indians in California.

According to the National Park Service, in their official online history of the Indigenous people of California:

In 1860, the law of 1850 was amended to state that Indian children and any vagrant Indian could be put under the custody of Whites for the purpose of employment and training. Under the law, it was possible to retain the service of Indians until 40 years of age for men and 35 years of age for women. This continued the practice of Indian slavery and made it legal for Indians to be retained for a longer period of time and be taken at a younger age.

In further documenting the treatment of Indigenous people by Americans after 1845, The Parks Service history states:

The Park Service history goes on to state:

In the early 1880s, Helen Hunt Jackson wrote A Century of Dishonor and sent a copy of her book to each United States congressman. She was then appointed to a commission to examine the condition of Indians in Southern California. Her visits resulted in The Report on the Condition and Needs of the Mission Indians of California, by special agents Helen Jackson and Abbot Kinney. The report summarized the problems and concerns of Southern California Indians; many of the conditions outlined in the report, however, were applicable to all California Indians. The report noted that Indians had been continually displaced from their land. She also noted that while many Indians had taken "immoral" paths, others had chosen the responsibilities of herding animals and raising crops. In her report, she also noted that the United States government had done little to right the wrongs of the past. While Jackson did not solve all the problems of Southern California Indians, her work did bring their concerns to the attention of the American public and Congress.

The National Park Service history continues:

One recurring concern was the lack of education and training necessary for survival in American society. The government, as well as Jackson, saw education as a way of assimilating Indians into the mainstream of United States society.

The period began of establishing "Indian Schools" to strip the tribe member of his or her identity as a member of the tribe began.

Reports from the Secretary of the Interior and the Bureau of Indian Affairs at that time expressed the goals of the government in relation to the educational process. In 1908, one report stated, "the rooms held three or four each and it was arranged that no two tribes were placed in the same room. This not only helped in the acquirement of English, but broke up tribal and race clannishness, a most important victory in getting Indians toward real citizens." (Spicer, 1969:235) An earlier report stated, "I can see no reason why a strong government like ours should not govern and control them [Indians] and compel each one to settle down and stay in one place, his own homestead, wear the white man's clothing, labor for his own support, and send his children to school." (Spicer, 1969:236) Other people had even stronger ideas. For instance, George Ellis, in his book, The Red Man and the White Man in North America, wrote, "The Indian must be made to feel he is in the grasp of a superior." (Ellis 1882:572) In opposition to this view, the Indian Rights Association was formed in 1882. This Indian advocate group would play a powerful role in formulating Indian policy in upcoming years.

Author's Note: This era of sending Indigenous children off their reservation and away from their family to boarding school was the single most traumatic experience most Indigenous people report in their lives. The actions of cutting their hair, prohibiting them from speaking their native language, and not allowing any action that could be interpreted as coming from their home tribe effective caused a whole generation of children to forget their language and spirituality and to be thought of as not fitting in with the tribe members who avoided "Indian Boarding Schools." This governmental action, along with breaking reservations into parcels of land to be sold constituted a disorientation of tribal life not dissimilar to the Nazis in Germany with their marking Judaic citizens with identification, banishing them to a common ghetto, and forcing them to leave their homes or be liquidated. In the case of Indigenous people, boarding school former students cite feelings of alienation, isolation, and having there culture ripped away, leaving them in a horrible netherworld somewhere between White and Red cultures. The resulting anguish and anger led tribal members to become hostile in most cases, and in rare cases violent.

While the approaches differed, all agreed that education was necessary. "In California, three types of educational programs were established for native peoples. The first was the Federal Government reservation day school. The second type was the boarding school, fashioned after Carlisle. And finally, the nearby public school that allowed Indians to attend began a slow, though steady, increase in popularity among policy makers." (Heizer, 1978:115) While the public schools seemed the best alternative, most Indians did not have the right to attend these schools until the 1920s.

In 1881, an elementary school system for Indians was established in California. However, the Indians soon recognized that the schools were a threat to their culture, as well as to the tribe as a political unit. "As a result, considerable resistance to the schools developed. Native peoples destroyed the day school at Potrero in 1888, and burned the school at Tule River in 1890. At Pachanga, a Luiseno named Venturo Molido, burned the school and assassinated the school teacher in 1895." (Heizer, 1978:115)

Here is the result of establishing Boarding Schools for Indigenous children:

Much of the destruction and violence could have been avoided if the school system and the government had recognized the great importance the Indians placed on being able to maintain their cultural beliefs. In 1891, school attendance was made mandatory. But while attendance was mandatory, there were still Indian children who did not attend.

As many Indigenous People know all too well:

The major tool the government used in trying to assimilate Indigenous persons during this time was the General Allotment Act of 1887, also known as the Dawes Act, which appeared to be generally advantageous to Indians. However, the major intent of the act was to break down the role of tribal government. The act itself provided that each Indian living on a reservation would receive a 160-acre allotment of land per family unit, and each single man would receive 80 acres if the reservation had enough land. If there was not enough land, other provisions were made. Indians not residing on a reservation would be entitled to settle on any surveyed or unsurveyed government lands not appropriated. The lands allotted would be held in trust for 25 years by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. If all other provisions of the act were met, that is, if the Indians made use of the lands for agriculture and became self-sufficient, then the land would become the property of the individual. "Native people understood full well the implications of allotment and offered considerable resistance. Nevertheless, the Bureau of Indian Affairs began ordering allotments of various sizes at Rincon, Morongo, and Pala Reservations in 1893. . . . The next year, allotments were begun at Round Valley Reservation. By the turn of the century, 1,614 individual allotments were made among eight reservations in the state." (Heizer, 1978:117)

Long before the passage of the Dawes Act, people recognized that problems would occur from its implementation. In 1881, Senator Henry Moore Teller of Colorado spoke in opposition to an earlier form of the Allotment Act. Senator Teller concluded, "If I stand alone in the Senate, I want to put upon the record my prophecy in this matter, that when 30 or 40 years shall have passed and these Indians shall have parted with their title, they will curse the hand that was raised professedly in their defense to secure this kind of legislation, and if the people who are clamoring for it understood Indian character and Indian laws, and Indian morals, and Indian religion, they would not be here clamoring for this at all." (Spicer, 1969:234) The senator would soon be proven correct.

Other Indians, such as the Cupenos from Warner Springs, chose to fight for their lands in the courts. With the assistance of the Indian Rights Association, they began a suit to stop their eviction from their home at the Warner Ranch. In 1888, they won a favorable decision which temporarily stopped their eviction. However, the case was appealed to the United States Supreme Court, and in 1903, the Cupenos were evicted from their home.

Some tribes chose to purchase land for their tribe:

Still other Indians chose to purchase land which was once theirs and reside on it. However, not every transaction was fair. In 1904, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that Indians who bought land from Whites were being dispossessed by the heirs of the granters, who gave no valid titles. "The Northern California Indian Association reported that about 10,000 Indians lived on land to which whites hold title. They were subject to eviction 'at any time.' The Indians are recognized for what they are not, usually competent to compete with white men in economic struggle. . . . Congress should buy lands for Indians in locations where they now are and allot them small farms in severalty. . . . It is also asked that their status as to citizenship be satisfactorily established. This petition is now before congress. It should be granted for justice and honesty. . . ." (San Francisco Chronicle, 1904). The struggle for homes would continue.

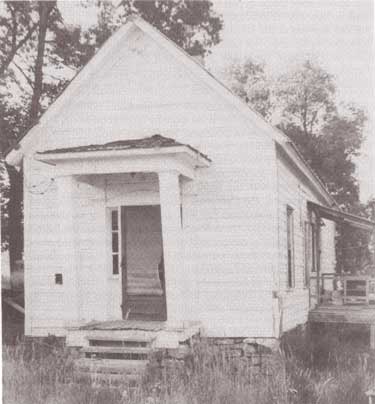

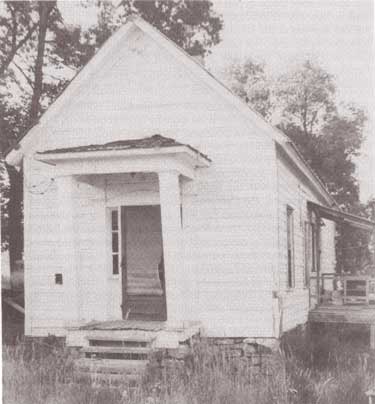

Old School House at Ft. Bidwell, Modoc County

Indian Grinding Rock State Historic Park, Amador County

Then, in 1950, the BIA established a job-placement program . . . [and] the program to assimilate Indians into the mainstream expanded from that point. Strangely, the BIA didn't keep records of its relocation pro gram, but nearly 100,000 Indians were relocated to California between 1952-1968 to find employment lacking on reservations. . . . " (Sacramento Bee, Sept. 6, 1982, p. 23) Indian people who had lived on reservations were now faced with the new problems of living in an urban environment and the inability to find services. Many were just not ready to live in a city.

Ya-Ka-Ama Indian School, Sonoma County

1. Ahwahnee, Mariposa County

2. Alcatraz, San Francisco

3. Anderson Marsh, Lake County

4. Angel Island, Marin County

5. Anoyum, San Diego County

6. Bald Rock Dome, Butte County

7. Black Mountain, San Luis Obispo County

8. Bloody Island, Lake County

9. Bryte Memorial Building, Yolo County

10. Camp Hill, San Luis Obispo County

11. Captain Jack's Stronghold, Modoc County

12. Channel Islands, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, and Ventura counties

13. Chaw'se/Indian Grinding Rock State Historic Park, Amador County

14. Cherokee, Butte County

15. Chimney Rock, San Luis Obispo County

16. Cho-Lollo, Tulare County

17. Cupa, San Diego County

18. D-Q University, Yolo County

19. Dana Point, Orange County

20. Dry Creek Valley, Sonoma County

21. El Scorpion Ranch, Los Angeles County

22. Estens and Kuvuny, Ventura County

23. Ferndale Ranch, Ventura County

24. Foresta Big Meadow, Mariposa County

25. Fort Bidwell Boarding School, Modoc County

26. Fort Bidwell School, Modoc County

27. Fort Gaston, Humboldt County

28. Frank Day's Home, Butte County

29. Gabriel's Grave, Monterey County

30. Glen Eden Springs, Riverside County

31. Greenville Meeting Hall, Plumas County

32. Gunther Island, Humboldt County

33. Helo/Mescalitan Island, Santa Barbara Island

34. Herbert Young's Residence, Butte County

35. Hilltop Tavern, Alameda County

36. Hopland High School, Mendocino County

37. Humqaq, Santa Barbara County

38. Hunting Blinds, Modoc County

39. Ishi's Hiding Place, Butte County

40. Knights Ferry, Stanislaus County

41. La Casa Grande, Sonoma County

42. La Jolla Village, San Diego County

43. Lake County Courthouse, Lake County

44. Las Viejas Mission, San Diego County

45. Madonna Mountain, San Luis Obispo County

46. Malki Museum, Riverside County

47. Manchester Reservation School, Mendocino County

48. Manchester Round House, Mendocino County

49. Mankins Ranch, Plumas County

50. Marie Potts' Home, Sacramento County

51. Mechoopda Indian Rancheria, Butte County

52. Mutamai, San Diego County

53. Mesa Grande Street, San Diego County

54. Mount Diablo, Contra Costa County

55. Nome Lackee Indian Reservation, Tehama County

56. North Fork School, Madera County

57. Old Kashia Elementary School, Sonoma County

58. Old Spanish Town, Santa Barbara County

59. Old Tule Reservation, Tulare County

60. Onomyo, Santa Barbara County

61. Painted Cave, Monterey County

62. Painted Caves, San Luis Obispo County

63. Pate Valley, Tuolumne County

64. Pete's Adobe, San Diego County

65. Place Where They Burnt the Digger, Amador County

66. Port San Luis, San Luis Obispo County

67. Quechla, San Diego County

68. Ramona Bowl, Riverside County

69. Rancho Canada Larga, Ventura County

70. Re-kwoi, Del Norte County

71. Rice Canyon Petroglyph Area, Lassen County

72. Roberts House, El Dorado County

73. Rogerio's Rancho, Los Angeles County

74. Round Valley Commissary, Mendocino County

75. Round Valley Flour Mill, Mendocino County

76. Round Valley Methodist Church, Mendocino County

77. Rust's Cemetery, Mariposa County

78. San Pasqual Battlefield State Historic Park, San Diego County

79. San Pasqual Cemetery, San Diego County

80. Santa Lucia Peak, Monterey County

81. Santa Rosa Rancheria, Kings County

82. Sherman Institute, Riverside County

83. Shisholop, Ventura County

84. Sloughhouse, Sacramento County

85. Paauw/Smith, San Diego County

86. Smith River Shaker Church, Del Norte County

87. Sonoma Barracks, Sonoma State Historic Park, Sonoma County

88. Squem, Monterey County

89. State Capitol, Sacramento County

90. Sutter's Fort, Sacramento County

91. Takimildin, Humboldt County

92. Tejon Indian Reservation, Kern County

93. Tischler Rock, Orange County

94. Tommy Merino's Home, Plumas County

95. Toro Creek, San Luis Obispo County

96. Trabuco Adobe, Orange County

97. Tulapop, Los Angeles County

98. Viejas V.F.W., San Diego County

99. Wilson Cemetery, Mariposa County

100. Wilton Baseball Field, Sacramento County

101. Ya-Ka-Ama, Sonoma County

102. Yosemite Rancheria, Mariposa County2

The West As a Moving Target

The boundary of the Western United States has moved westward several times since it was first identified. To an Eighteenth Century Virginian, such as Thomas Jefferson, the West was a wilderness populated by hostile Indigenous tribes. The West was also viewed as an open region, populated by "backward savages." The US governmental view was that the Indigenous tribes were not "using" the land beyond the Cumberland Gap, one of the West's first identified mountain passes. Indigenous lands were invaded by White settlers who turned old growth forests into farmland. The war with Western Indigenous tribes had moved further West. This type of invasion was to be repeated with westward expansion as a result throughout the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries.

Manifest Destiny Protecting Migrating Settlers

The "Unconquered West" was to become the target of seekers of gold, arable land, and a national attitude that was labeled "Manifest Destiny."

Manifest Destiny as Myth

The philosophy called Manifest Destiny was one of the pillars of the ideological superstructure used to expand European-American control over the North American continent. That the US government supported Westward expansion was never seriously questioned. Although Manifest Destiny did not enter the American Mythical nomenclature until the Mid Nineteenth Century, the assumption of European-American entitlement to all of North (and South) American lands was embedded in European-American public discourse. This was because "savages" did not make use of their lands in a manner acceptable to the USA, nor did those Indigenous peoples have a concept of land ownership in their traditional beliefs. The God of Abraham, Jesus, and The Prophet was also the European-American God who was personalized by the Torah, Bible, and Quran. Cultural Imperialism became the policy of the US government with respect to Westward Expansion.

The oral traditions of Indigenous tribes in the time prior to and during European-American hegemony westward were as varied as the tribes themselves. Each tribe had a language that may have been similar to other tribes' languages, but was different enough to require bilingual interpreters or sign language communication. There were and are agreements between various tribes that spanned centuries. The Iriquois Confederation of Five Civilized Tribes predated European-American presence by a century. This cooperative agreement, among many others, was evidence that contradicted the second Western American Myth...the "Noble Savage."

Indigenous Peoples As "Primitive Noble Savages"

The Noble Savage became a primary archetype strengthened by authors like James Fenimore Cooper. There has been a long disagreement among researchers in anthropology as to whether non European-American peoples were similar to or different from Europeans prior to first contact with European-American civilizations.

Stereotype Noble Savage from Deer Slayer by James Fenimore Cooper

The Noble Savage myth dates from the Seventeenth Century, and emerged from Romanticism. That the idea of a Noble Savage existed did not stop the US government from promulgating the idea that Indigenous tribes needed to be assimilated into European-American culture with their own beliefs to be eradicated.

Use of the Noble Savage Stereotype as Marketing Tool in 19th Century

Suffice to say that a tribe of Indigenous people, if invaded by European-American culture, will strive to keep secret the beliefs that are most precious to their culture. Perhaps it was this self-preservational dynamic of Indigenous tribes' spiritual, family, cultural, governing, and language structure and beliefs throughout the world that led European-Americans to become determined to erase Indigenous cultures with the purpose of assimilation of such peoples into European-American culture. This process was fairly similar worldwide through the destruction of the very foundations of Indigenous culture...spiritual beliefs, extended clan family structure, tribal decision-making, and most importantly, their native language.

The European-American "Progress Marches On" Myth

The systematic process of Indigenous Cultural destruction was justified by another Western Myth, the Superiority of European-American Culture over Indigenous Cultures. The arrogant belief that European-American cultures were the key to bringing the Indigenous tribes into what came to be called "The Melting Pot" reflected the Cultural Imperialism of the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth centuries of the Americans of European-American descent.

Progress became intertwined with the Protestant Ethic in the Nineteenth Century, and pursuit of wealth became interwoven with rapid advancements in technology. As improvements in agricultural technology, communication, transportation, and manufacturing emerged, the ease of living in each phase of the New West improved. The Indigenous tribes of North America were gradually stripped of their culture, sources of sustenance, hunting and fishing land, and health. A combination of gradual incursion, curtailment of the various tribes' ability to migrate with the seasons, phony promises made in treaties not worth the paper they were signed on, and harassment leading to further genocide stripped the tribes of the very characteristics and customs that defined them in how they saw themselves and how other tribes saw them.

During the Presidency of Andrew Jackson,the Southeastern regional US Indigenous tribes were ordered to be relocated to the land beyond the Louisiana Purchase to enable the expansion of agriculture and slavery into those tribes' lands. Although the Trail of Tears is the most famous example of President Andrew Jackson's cruel and imperialistic ejection of tribes from their homelands, other tribes experienced similar relocation. The purpose of creation of Indian Territory was to ostensibly reserve that land for Indigenous peoples, but the reality was that fortune seekers, farmers, and riff raff invaded Indian Territory and sabotaged the intended setting aside of land for tribal settlements. This behavior was pervasive throughout the Nineteenth Century.

In the first decade of the Nineteenth Century, Napoléon sold France's Louisiana lands to Thomas Jefferson's United States, leading to the invasion of Louisiana by Lewis and Clark. Their exploration was first contact between the US Government and Missouri and Columbia River drainage area Indigenous Tribes. The tribes that the Lewis and Clark Expedition encountered were generally receptive with a few exceptions. The rivers that flowed into the Missouri and Columbia Rivers were mapped, detailed notation and drawings were recorded, and flora and fauna were carefully described.

Manifest Destiny as Defined by Indigenous Tribes

As a rule, Americans other than Indigenous Tribal members have viewed the Lewis and Clark Expedition as a heroic exploration of new USA Westward expansion. But within a generation, the Mandan Tribe who hosted the Americans in their first Expedition winter were dead. Within two generations, the Nez Perce Tribe, who gave the Expedition the horses they desperately needed to proceed onward to the Pacific Ocean, were brutally and forcefully evicted from their Wallowa Valley lands by the US cavalry.

The US Army's use of weapons far advanced over those of Indigenous tribes made contact with US troops fatal for too many Indigenous men, women and children to count. The transcontinental railroad was built through hunting grounds. Various mercantile trails and cattle trails crisscrossed what was the edge of the American West. In less than 100 years the Americans had evicted the Southern US tribes, decimated the Northeastern and also the tribes from what is now called the American Midwest. The bison, now America's National Animal, was the source of nearly every tool or food that Northern Plains tribes used. Hundreds of treaties were signed and then broken by US Army officers and troops. Ironically, it was the Indigenous people who were labeled as dishonest.

Cultural Imperialism shoved tribes who were hunters and constantly moving from place to place into lands believed to be useless for American citizens. Labeled as reservations, the tribes were ordered to learn to be farmers on land unfit for growing crops. Tribes were relegated to eating spoiled meat and other food which was unfit for Caucasian consumption. Alcohol was provided to Indigenous people who had never been exposed to it. Rampant diseases, such as smallpox and measles and drinking were ignored by people paid to assist the tribes, often as government agents. Sacred lands, such as the Paha Sapa (Black Hills) were stolen and traditional spirituality ignored or discouraged. As the Nineteenth Century ended, Indigenous people in the USA numbered 250,000. This was down from an estimated 20 million people in the time of first contact with European-American civilizations. Several tribes were "delisted" from US Governmental Tribal lists. This meant that these tribes no longer were even eligible for reservations, medicine, and other life sustaining elements. Other tribes simply died out. The saga of Ishi, a member of a California tribe, the Yahi, poignantly documented his last years as the sole surviving member, residing in a museum as a living exhibit in San Francisco. That Ishi became the last member of the Yahi Clan of the Yana Tribe of California reflects the chaos and danger that Indigenous people faced when having first contact with Caucasians. Later in this article, the history of the State of California will be examined through use of prior scholarly research. See illustrations below:

In 19th Century America, Indigenous people were not thought to be competent to manage their own affairs, and even the sympathetic press referred to them as "savages"

The Area of California in Which Ishi's tribe, the Yana Lived

Ishi, a man without his people lived in a museum as a human exhibit

Here is his death mask

For more information on Ishi please double click the link to this excellent overview of his life: Ishi's story told at the time he was alive

The annexation of Texas in 1845 into the United States led to systematic military engagement with Indigenous tribes such as the Comanche. Other tribes were also driven from their traditional lands even more rapidly than the Comanche. The demise of the bison from the Southern Plains occurred more rapidly than in the Dakotas, Wyoming, Nebraska, and Montana. The decline of the Southern Plains tribes led to all of their former territories being changed into large ranches or subsistence farming. Although the US government supported this type of farming through the Homestead Act, the lower precipitation and droughts caused hundreds of thousands of square miles becoming unusable and essentially dead. Acreage in such regions remain ruined with little hope for restoration of the tall grass prairies before invaders took the land and ruined it.

Diagram of Western Plains with The Comanche Territory in Circle -Comancheria

Comanche Wars-Battle of Plum Creek

Note the Top Hats on Warriors

Tribes in the arid Southwest were generally kept in their traditional lands. Pueblos were protected by their history of being deeded by the Spanish Kinghe famous s through land grants, which were honored by treaty after the Mexican War. The Navajo (Di'neh) were settled on a 25,000 square mile reservation in New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah. This happened after a large portion of the tribe endured the Long Walk from their lands to Fort Sumner, New Mexico. The famous frontiersman Kit Carson along with the US Army conducted a slash and burn campaign against the Navajo, marched them some 400 miles in freezing weather, and then the tribe was told to learn how to farm on the arid semi-desert of New Mexico's Llano Estacado. Some 3000 Navajo died there due to starvation, US Army neglect, and diseases that rampages through the tribe.

The Navajo (Di' Neh) Tribe in Ft. Sumner NM after The Long Walk

Many children and elderly died in a failed attempt to turn the tribe into farmers

Plains tribes engaged Cavalry soldier in the "Eight Year Indian War with several brilliant warriors and

chiefs over the length of the fighting. Now famous warriors and chiefs tactics are studied by military intructors

With the massacre at the Little Big Horn and the 7th regiment's deaths, commanded by Custer and Chief Gall respectively,

the United States as a whole was outraged. Senior Army staff, as ordered by President Grant intensified the "Indian War" against tribes that had not submitted to stay on a reservation. From Washington DC downward, the free tribes, the Lakota, Apaches, Northern Cheyenne, and others faced a search and destroy mission comparable to hunting down ISIS in this time. The remaining free Indigenous tribes kept their way of life for as long as they could.

Map of the Little Bighorn Engagement

Courtesy of National Park Service

The National Park Service has placed a memorial for the Indigenous warriors killed at Little Bighorn

Photo Courtesy of the National Park Service

Northern Cheyenne Survivors of Little Big Horn in 1926

Photo Courtesy of the National Park Service

Important leaders such as President Grant appointed several seasoned leaders, most notably General Sheridan, whose battle tactics were important in the US Civil War. Treaties the United States Government initiated had been broken repeatedly by the United States. The Smithsonian has identified 503 broken treaties with various tribes from 1778 to the present day. This list of broken treaties comes from the National Archive and may be viewed in Wikipedia. This list of broken treaties may be found below:

If you survive looking at the list of broken treaties....this blog article continues below

1778–1799

1800–1809

1810–1819

1820–1829

1830–1839

| Year | Date | Treaty Name | Alternative Treaty Name | Statutes | Land Cession Reference (Royce Area) | Tribe(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1830 | July 15 | Treaty of Prairie du Chien | Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes, etc., Fourth Treaty of Prairie du Chein | 7 Stat. 328 | 151 | Sac and Fox, the Mdewakanton, Wahpekute, Wahpeton and Sisiton Sioux, Omaha, Ioway, Otoe and Missouria |

| 1830 | September 27 | Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek | Treaty with the Choctaw | 7 Stat. 333 | Choctaw | |

| 1830 | August 31 | Treaty of Franklin | Treaty with the Chickasaw | N/A | ||

| 1830 | September 1 | Supplement to the Treaty of Franklin | Supplemental Treaty with the Chickasaw | N/A | ||

| 1831 | February 8 | Treaty of Washington | Treaty with the Menominee | 7 Stat. 342 | Menomini | |

| 1831 | February 17 | Supplement to the Treaty of Washington | Treaty with the Menominee | 7 Stat. 346 | Menomini | |

| 1831 | February 28 | Treaty of Washington | Treaty with the Seneca | 7 Stat. 348 | Seneca nation | |

| 1831 | July 20 | Treaty of Lewistown | Treaty with the Seneca, etc. | 7 Stat. 351 | Seneca nation, Shawnee | |

| 1831 | August 8 | Treaty of Wapakoneta | Treaty with the Shawnee | 7 Stat. 355 | Shawnee | |

| 1831 | August 30 | Treaty of Miami Bay | Treaty with the Ottawa | 7 Stat. 359 | Ottawa | |

| 1832 | January 19 | Treaty with the Wyandot | 7 Stat. 364 | Wyandot | ||

| 1832 | March 24 | Treaty of Cusseta | Treaty with the Creeks | 7 Stat. 366 | Creek | |

| 1832 | May 9 | Treaty of Payne's Landing | Treaty with the Seminole | 7 Stat. 368 | Seminole | |

| 1832 | September 15 | Treaty with the Winnebago | 7 Stat. 370 | |||

| 1832 | September 21 | Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes | 7 Stat. 374 | |||

| 1832 | October 11 | Treaty with the Appalachicola Band | 7 Stat. 377 | |||

| 1832 | October 20 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | 7 Stat. 378 | |||

| 1832 | October 20 | Treaty with the Chickasaw | 7 Stat. 381 | |||

| 1832 | October 22 | Treaty with the Chickasaw | 7 Stat. 388 | |||

| 1832 | October 24 | Treaty with the Kickapoo | 7 Stat. 391 | |||

| 1832 | October 26 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | 7 Stat. 394 | |||

| 1832 | October 26 | Treaty with the Shawnee, etc. | 7 Stat. 397 | |||

| 1832 | October 27 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | 7 Stat. 399 | |||

| 1832 | October 27 | Treaty with the Kaskaskia, etc. | 7 Stat. 403 | |||

| 1832 | October 27 | Treaty with the Menominee | 7 Stat. 405 | |||

| 1832 | October 29 | Treaty with the Piankashaw and Wea | 7 Stat. 410 | |||

| 1832 | December 29 | Treaty with the Seneca and Shawnee | 7 Stat. 411 | |||

| 1833 | February 14 | Treaty with the Western Cherokee | 7 Stat. 414 | |||

| 1833 | February 14 | Treaty with the Creeks | 7 Stat. 417 | |||

| 1833 | February 18 | Treaty with the Ottawa | 7 Stat. 420 | |||

| 1833 | March 28 | Treaty with the Seminole | 7 Stat. 423 | |||

| 1833 | May 13 | Treaty with the Quapaw | 7 Stat. 424 | |||

| 1833 | June 18 | Treaty with the Appalachicola Band | 7 Stat. 427 | |||

| 1833 | September 21 | Treaty with the Oto and Missouri | 7 Stat. 429 | |||

| 1833 | September 26 | Treaty of Chicago | Treaty with the Chippewa, etc. | 7 Stat. 431 | Ottawa, Ojibwe and Potawatomi | |

| 1833 | October 9 | Treaty with the Pawnee | 7 Stat. 448 | |||

| 1834 | May 24 | Treaty with the Chickasaw | 7 Stat. 450 | |||

| 1834 | October 23 | Treaty with the Miami | 7 Stat. 458 | |||

| 1834 | December 4 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | 7 Stat. 467 | |||

| 1834 | December 10 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | 7 Stat. 467 | |||

| 1834 | December 16 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | 7 Stat. 468 | |||

| 1834 | December 17 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | 7 Stat. 469 | |||

| 1835 | July 1 | Treaty with the Caddo | 7 Stat. 470 | |||

| 1835 | August 24 | Treaty with the Comanche, etc. | 7 Stat. 474 | |||

| 1835 | December 29 | Treaty of New Echota | Treaty with the Cherokee | 7 Stat. 478 | Cherokee | |

| 1835 | March 14 | Treaty of Washington | Agreement with the Cherokee | N/A | ||

| 1836 | March 26 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | 7 Stat. 490 | |||

| 1836 | March 28 | Treaty of Washington | Treaty with the Ottawa, etc. | 7 Stat. 491 | Ottawa and Ojibwe | |

| 1836 | March 29 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | 7 Stat. 498 | |||

| 1836 | April 11 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | 7 Stat. 499 | |||

| 1836 | April 22 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | 7 Stat. 500 | |||

| 1836 | April 22 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | 7 Stat. 501 | |||

| 1836 | April 23 | Treaty with the Wyandot | 7 Stat. 502 | |||

| 1836 | May 9 | Treaty with the Chippewa | 7 Stat. 503 | |||

| 1836 | August 5 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | 7 Stat. 505 | |||

| 1836 | September 3 | Treaty with the Menominee | 7 Stat. 506 | |||

| 1836 | September 10 | Treaty with the Sioux | 7 Stat. 510 | |||

| 1836 | September 17 | Treaty with the Iowa, etc. | 7 Stat. 511 | |||

| 1836 | September 20 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | 7 Stat. 513 | |||

| 1836 | September 22 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | 7 Stat. 514 | |||

| 1836 | September 23 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | 7 Stat. 515 | |||

| 1836 | September 27 | Treaty with the Sauk and Fox Tribe | 7 Stat. 516 | |||

| 1836 | September 28 | Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes | 7 Stat. 517 | |||

| 1836 | September 28 | Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes | 7 Stat. 520 | |||

| 1836 | October 15 | Treaty with the Oto, etc. | 7 Stat. 524 | |||

| 1836 | November 30 | Treaty with the Sioux | 7 Stat. 527 | |||

| 1837 | January 14 | Treaty of Detroit | Treaty with the Chippewa | 7 Stat. 528 | ||

| 1837 | January 17 | Treaty of Doaksville | Treaty with the Choctaw and Chickasaw | 11 Stat. 573 | ||

| 1837 | February 11 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | 7 Stat. 532 | |||

| 1837 | May 26 | Treaty with the Kiowa, etc. | 7 Stat. 533 | |||

| 1837 | July 29 | Treaty with the Chippewa | 7 Stat. 536 | |||

| 1837 | September 29 | Treaty with the Sioux | 7 Stat. 538 | |||

| 1837 | October 21 | Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes | 7 Stat. 540 | |||

| 1837 | October 21 | Treaty with the Yankton Sioux | 7 Stat. 542 | |||

| 1837 | October 21 | Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes | 7 Stat. 543 | |||

| 1837 | November 1 | Treaty with the Winnebago | 7 Stat. 544 | |||

| 1837 | November 23 | Treaty with the Iowa | 7 Stat. 547 | |||

| 1837 | December 20 | Treaty with the Chippewa | 7 Stat. 547 | |||

| 1838 | January 15 | Treaty of Buffalo Creek | Treaty with the New York Indians | 7 Stat. 550 | Seneca, Mohwak, Cayuga, Oneida, Onondaga, Tuscarora | |

| 1838 | January 23 | Treaty of Saginaw | Treaty with the Chippewa | 7 Stat. 565 | ||

| 1838 | February 3 | Treaty of Washington | Treaty with the Oneida | 7 Stat. 566 | ||

| 1838 | October 19 | Treaty of Great Nemowhaw | Treaty with the Iowa | 7 Stat. 568 | ||

| 1838 | November 6 | Treaty of Wabash Forks | Treaty with the Miami | 7 Stat. 569 | ||

| 1838 | November 23 | Treaty of Fort Gibson | Treaty with the Creeks | 7 Stat. 574 | ||

| 1839 | January 11 | Treaty of Fort Gibson | Treaty with the Osage | 7 Stat. 576 | ||

| 1839 | February 7 | Supplement to the Treaty of Detroit | Treaty with the Chippewa | 7 Stat. 578 | ||

| 1839 | September 3 | Treaty of Stockbridge | Treaty with the Stockbridge and Munsee | 7 Stat. 580 11 Stat. 577 |

1840–1849

| Year | Date | Treaty Name | Alternative Treaty Name | Statutes | Land Cession Reference (Royce Area) | Tribe(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | November 28 | Treaty of the Wabash | Treaty with the Miami | 7 Stat. 582 | ||

| 1842 | Treaty with the Wyandot | |||||

| 1842 | May 20 | Treaty of Buffalo Creek | Treaty with the Seneca | 7 Stat. 586 | Seneca | |

| 1842 | October 4 | Treaty of La Pointe | Treaty with the Chippewa | 7 Stat. 591 | Ojibwe | |

| 1842 | October 11 | Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes | 7 Stat. 596 | |||

| 1843 | Agreement with the Delawares and Wyandot | |||||

| 1845 | Treaty with the Creeks and Seminole | |||||

| 1846 | Treaty with the Kansa Tribe | |||||

| 1846 | Treaty with the Comanche, Aionai, Anadarko, Caddo, etc. | |||||

| 1846 | Treaty with the Potawatomi Nation | |||||

| 1846 | Treaty with the Cherokee | |||||

| 1846 | Treaty with the Winnebago | |||||

| 1846 | November 21 | Bear Spring Treaty | Treaty with the Navajo | Navajo people | ||

| 1847 | Treaty with the Chippewa of the Mississippi and Lake Superior | |||||

| 1847 | Treaty with the Pillager Band of Chippewa Indians | |||||

| 1848 | August 6 | Treaty of Fort Childs | Treaty with the Pawnee – Grand, Loups, Republicans, etc. | 9 Stat. 949 | Pawnee | |

| 1848 | October 18 | Treaty with the Menominee | 9 Stat. 952 | Menominee | ||

| 1848 | November 24 | Treaty with the Stockbridge Tribe | 9 Stat. 955 | Stockbridge Indians (Mahican) | ||

| 1849 | Treaty with the Navaho | |||||

| 1849 | December 30 | Treaty of Albuquerque | Treaty with the Utah | 9 Stat. 974 | Ute |

1850–18591860–1869

| Year | Date | Treaty Name | Alternative Treaty Name | Statutes | Land Cession Reference (Royce Area) | Tribe(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | Treaty with the Wyandot | |||||

| 1851 | July 23 | Treaty of Traverse des Sioux | Treaty with the Sioux-Sisseton and Wahpeton Bands | Sioux | ||

| 1851 | August 5 | Treaty of Mendota | Treaty with the Sioux-Mdewakanton and Wahpakoota Bands | Sioux | ||

| 1851 | September 17 | Treaty of Fort Laramie | Treaty of Fort Laramie with Sioux, etc. | Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, Shoshone, Assiniboine, Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara | ||

| 1852 | Treaty with the Chickasaw | |||||

| 1852 | Treaty with the Apache | |||||

| 1853 | Treaty with the Comanche, Kiowa, and Apache | |||||

| 1853 | Agreement with the Rogue River (not ratified) | |||||

| 1853 | Treaty with the Rogue River, 1853 | |||||

| 1853 | Treaty with the Umpqua–Cow Creek Band | |||||

| 1854 | Treaty with the Oto and Missouri | |||||

| 1854 | Treaty with the Omaha | |||||

| 1854 | Treaty with the Delawares | |||||

| 1854 | Treaty with the Shawnee | |||||

| 1854 | Treaty with the Menominee | |||||

| 1854 | Treaty with the Iowa | |||||

| 1854 | Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes of Missouri | |||||

| 1854 | Treaty with the Kickapoo | |||||

| 1854 | Treaty with the Kaskaskia, Peoria, etc. | |||||

| 1854 | Treaty with the Miami | |||||

| 1854 | Treaty with the Creeks | |||||

| 1854 | September 30 | Treaty of La Pointe (1854) | Treaty with the Chippewa | Ojibwe | ||

| 1854 | Treaty with the Choctaw and Chickasaw | |||||

| 1854 | Treaty with the Rogue River, 1854 | |||||

| 1854 | Treaty with the Chasta, etc. | |||||

| 1854 | Treaty of Calapooia Creek | Treaty with the Umpqua and Kalapuya | ||||

| 1854 | Treaty with the Confederated Oto and Missouri | |||||

| 1854 | Treaty of Medicine Creek | Treaty with the Nisqualli, Puyallup, etc. | Nisqually, Puyallup and Squaxin Island | |||

| 1855 | Willamette Valley Treaty of 1855 Treaty of Dayton | Treaty with the Kalapuya, etc. | ||||

| 1855 | January 22 | Treaty of Point Elliott | Treaty with the Dwamish, Suquamish, etc., Point Elliott Treaty | Duwamish, Suquamish, Snoqualmie, Snohomish, Lummi, Skagit, Swinomish | ||

| 1855 | Treaty with the S'klallam | |||||

| 1855 | January 31 | Treaty of Washington | Treaty with the Wyandot | Wyandot | ||

| 1855 | January 31 | Treaty of Neah Bay | Treaty with the Makah | Makah | ||

| 1855 | February 22 | Treaty of Washington | Treaty with the Chippewa | Ojibwe (Mississippi and Pillager) | ||

| 1855 | February 27 | Treaty of Washington | Treaty with the Winnebago | Ho-chunk | ||

| 1855 | Treaties of Walla Walla | Treaty with the Wallawalla, Cayuse, etc. | Cayuse, Nez Perce, Umatilla, Walla Walla and Yakama | |||

| 1855 | Treaty with the Yakima | |||||

| 1855 | Treaty with the Nez Perces | |||||

| 1855 | June 22 | Treaty of Washington | Treaty with the Choctaw and Chickasaw | Choctaw and Chickasaw | ||

| 1855 | Treaty with the Tribes of Middle Oregon | |||||

| 1855 | Treaty with the Quinaielt, etc. | |||||

| 1855 | July 16 | Treaty of Hellgate | Treaty with the Flatheads, etc. | Bitterroot Salish, Kootenai and Pend d'Oreilles | ||

| 1855 | Treaty with the Ottawa and Chippewa | |||||

| 1855 | Treaty with the Chippewa of Sault Ste. Marie | |||||

| 1855 | Treaty with the Chippewa of Saginaw, etc. | |||||

| 1855 | Treaty with the Blackfeet | |||||

| 1855 | Treaty with the Molala | |||||

| 1856 | Treaty with the Stockbridge and Munsee | |||||

| 1856 | Treaty with the Menominee | |||||

| 1856 | Treaty with the Creeks, etc. | |||||

| 1857 | Treaty with the Pawnee | |||||

| 1857 | Treaty with the Seneca, Tonawanda Band | |||||

| 1858 | Treaty with the Ponca | |||||

| 1858 | Treaty with the Yankton Sioux | |||||

| 1858 | Treaty with the Sioux | |||||

| 1858 | Treaty with the Sioux | |||||

| 1859 | Treaty with the Winnebago | |||||

| 1859 | Treaty with the Chippewa, etc. | |||||

| 1859 | Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes | |||||

| 1859 | Treaty with the Kansa Tribe |

1860–1869

| Year | Date | Treaty Name | Alternative Treaty Name | Statutes | Land Cession Reference (Royce Area) | Tribe(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | Treaty with the Delawares | |||||

| 1861 | Treaty with the Arapaho and Cheyenne | |||||

| 1861 | Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes, etc. | |||||

| 1861 | Treaty with the Delawares | |||||

| 1861 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | |||||

| 1862 | Treaty with the Kansa Indians | |||||

| 1862 | Treaty with the Ottawa of Blanchard's Fork and Roche de Boeuf | |||||

| 1862 | Treaty with the Kickapoo | |||||

| 1863 | Treaty with the Chippewa of the Mississippi and the Pillager and Lake Winnibigoshish Bands | |||||

| 1863 | June 9 | Treaty with the Nez Perce | 14 Stat. 647 | Nez Perce | ||

| 1863 | Treaty with the Eastern Shoshoni | |||||

| 1863 | Treaty with the Shoshoni-Northwestern Bands | |||||

| 1863 | Treaty with the Western Shoshoni | |||||

| 1863 | Treaty with the Chippewa-Red Lake and Pembina Bands | |||||

| 1863 | Treaty with the Utah-Tabeguache Band | |||||

| 1863 | Treaty with the Shoshoni-Goship | |||||

| 1864 | Treaty with the Chippewa—Red Lake and Pembina Bands | |||||

| 1864 | Treaty with the Chippewa, Mississippi, and Pillager and Lake Winnibigoshish Bands | |||||

| 1864 | Treaty with the Klamath, etc. | |||||

| 1864 | Treaty with the Chippewa of Saginaw, Swan Creek, and Black River | |||||

| 1865 | Treaty with the Omaha | |||||

| 1865 | Treaty with the Winnebago | |||||

| 1865 | Treaty with the Ponca | |||||

| 1865 | Treaty with the Snake | |||||

| 1865 | Treaty with the Osage | |||||

| 1865 | Treaty with the Sioux—Miniconjou Band | |||||

| 1865 | Treaty with the Sioux—Lower Brule Band | |||||

| 1865 | Agreement with the Cherokee and Other Tribes in the Indian Territory | |||||

| 1865 | Treaty with the Cheyenne and Arapaho | |||||

| 1865 | Treaty with the Apache, Cheyenne, and Arapaho | |||||

| 1865 | Treaty with the Comanche and Kiowa | |||||

| 1865 | Treaty with the Sioux-Two-Kettle Band | |||||

| 1865 | Treaty with the Blackfeet Sioux | |||||

| 1865 | Treaty with the Sioux-Sans Arc Band | |||||

| 1865 | Treaty with the Sioux-Hunkpapa Band | |||||

| 1865 | Treaty with the Sioux-Yanktonai Band | |||||

| 1865 | Treaty with the Sioux-Upper Yanktonai Band | |||||

| 1865 | Treaty with the Sioux-Oglala Band | |||||

| 1865 | Treaty with the Middle Oregon Tribes | |||||

| 1866 | Treaty with the Seminole | |||||

| 1866 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | |||||

| 1866 | Treaty with the Chippewa—Bois Fort Band | |||||

| 1866 | Treaty with the Choctaw and Chickasaw | |||||

| 1866 | Treaty with the Creeks | |||||

| 1866 | Treaty with the Delawares | |||||

| 1866 | Agreement at Fort Berthold, Appendix | |||||

| 1866 | Treaty with the Cherokee | |||||

| 1867 | Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes | |||||

| 1867 | Treaty with the Sioux—Sisseton and Wahpeton Bands | |||||

| 1867 | Treaty with the Seneca, Mixed Seneca and Shawnee, Quapaw, etc. | |||||

| 1867 | Treaty with the Potawatomi | |||||

| 1867 | Treaty with the Chippewa of the Mississippi | |||||

| 1867 | October 21 | Medicine Lodge Treaty | Treaty with the Kiowa and Comanche | 15 Stat. 581 | ||

| 1867 | Treaty with the Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache | |||||

| 1867 | Treaty with the Cheyenne and Arapaho | |||||

| 1868 | Treaty with the Ute | |||||

| 1868 | Treaty with the Cherokee | |||||

| 1868 | April 29 | Treaty of Fort Laramie | Treaty with the Sioux—Brule, Oglala, Miniconjou, Yanktonai, Hunkpapa, Blackfeet, Cuthead, Two Kettle, Sans Arcs, and Santee—and Arapaho | 15 Stat. 635 | ||

| 1868 | Treaty with the Crows | |||||

| 1868 | Treaty with the Northern Cheyenne and Northern Arapaho | |||||

| 1868 | June 1 | Treaty of Fort Sumner | Treaty with the Navaho; Navajo Treaty of 1868; Treaty of 1868; Treaty of Hwéeldi | 15 Stat. 667 | Navajo | |

| 1868 | Treaty with the Eastern Band Shoshoni and Bannock | |||||

| 1868 | August 13 | Treaty of Lapwai | Treaty with the Nez Perce | 15 Stat. 693 | Nez Perce |

1870–1879

Treaty-making between various Native American governments and the United States officially concluded on March 3, 1871 with the passing of the United States Code Title 25, Chapter 3, Subchapter 1, Section 71 (25 U.S.C. § 71). Pre-existing treaties were grandfathered, and further agreements were made under domestic law.

| Year | Date | Treaty Name | Alternative Treaty Name | Statutes | Land Cession Reference (Royce Area) | Tribe(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | January 31 | Executive Order | N/A | 527, 528 | San Pasqual and Pala Valley Mission Indians | |

| 1870 | March 30 | Executive Order | N/A | Round Valley Indian Reservation | ||

| 1870 | April 12 | Executive Order | N/A | 620, 621 | Arikara, Gros Ventre, and Mandan | |

| 1870 | April 12 | Executive Order | N/A | 529 | Arikara, Gros Ventre, and Mandan | |

| 1870 | July 15 | Act of Congress | 16 Stat. 359 | 650 | Kickapoo of Texas and Mexico | |

| 1870 | July 15 | Act of Congress | 16 Stat. 362 | 534 | Great and Little Osage | |

| 1870 | July 15 | Act of Congress | 16 Stat. 362 | 530 | Great and Little Osage | |

| 1871 | February 6 | Act of Congress | 16 Stat. 404 | 403 | Stockbridge and Munsee | |

| 1871 | March 3 | Act of Congress | United States Code Title 25, Chapter 3, Subchapter 1, Section 71 | 16 Stat. 566 | ||

| 1871 | March 3 | Act of Congress | 16 Stat. 569 | 650 | Kickapoo of Texas and Mexico | |

| 1871 | March 14 | Executive Order | N/A | 537 | Paiute, Snake, Shoshoni | |

| 1871 | March 27 | Executive Order | N/A | 534 | Osage | |

| 1871 | November 9 | Executive Order | N/A | 531 | Southern Apache | |

| 1871 | November 9 | Executive Order | N/A | 573, 603 | Apache | |

| 1871 | November 9 | Executive Order | N/A | 541 | Apache | |

| 1871 | November 9 | Executive Order | N/A | 582 | Apache | |

| 1871 | December | Memorandum | N/A | Methow, Okanagan, Kootenay, Pend d'Oreille, Colville, North Spokane, San Poeil et al. | ||

| 1872 | April 9 | Executive Order | N/A | 533 | Methow, Okanagan, et al. | |

| 1872 | April 23 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 55 | 566 | Ute | |

| 1872 | May 8 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 85 | Kaw | ||

| 1872 | May 23 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 159 | 506 | Potawatomi and Absentee Shawnee | |

| 1872 | May 29 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 190 | Lake Superior Chippewa | ||

| 1872 | May 29 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 190 | Cheyenne and Arapaho | ||

| 1872 | June 1 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 213 | 256 | Miami (Meshin-go-mesia's band) | |

| 1872 | June 5 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 228 | 534 | Great and Little Osage | |

| 1872 | June 5 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 228 | 535 | Kaw | |

| 1872 | June 5 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 266 | Flathead | ||

| 1872 | June 7 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 281 | Sisseton and Wahpeton Sioux | ||

| 1872 | June 10 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 381 | Ottawa and Chippewa | ||

| 1872 | June 10 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 388 | Ottawa of Blanchards Fork and Roche de Boeuf | ||

| 1872 | June 10 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 391 | Omaha, Pawnee, Oto, Missouri, and Sac and Fox of the Missouri | ||

| 1872 | July 2 | Executive Order | N/A | 533, 536 | Methow, Okanaga, et al. | |

| 1872 | September 12 | Executive Order | N/A | 537, 638, 646 | Paiute, Snake, and Shoshoni | |

| 1872 | September 20 | Agreement | Agreement with the Sisseton and Wahpeton Bands of Sioux Indians | Rev. Stat 1050 | 538 | Sisseton and Wahpeton Bands of Sioux |

| 1872 | September 26 | Agreement | 18 Stat. 291 | 539, 540 | Shoshoni | |

| 1872 | October 19 | Agreement | N/A | 540A | Wichita and affiliated bands | |

| 1872 | October 26 | Executive Order | N/A | Makah | ||

| 1872 | December 14 | Executive Order | N/A | 541, 600 | Apache | |

| 1872 | December 14 | Executive Order | N/A | Apache | ||

| 1873 | January 2 | Executive Order | N/A | Makah | ||

| 1873 | January 9 | Executive Order | N/A | 607 | Tule River, King's River, Owen's River, et al. | |

| 1873 | February 14 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 456 | 538 | Sisseton and Wahpeton Sioux | |

| 1873 | February 19 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 466 | 249 | New York Indians | |

| 1873 | March 1 | Executive Order | N/A | 337 | Lac Courte Oreille Band of Chippewa | |

| 1873 | March 3 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 539 | 542 | Pembina Chippewa | |

| 1873 | March 3 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 631 | 330 | Miami | |

| 1873 | March 3 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 633 | 543 | Creek and Seminole | |

| 1873 | March 3 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 626 | 544, 583 | Round Valley Indian Reservation | |

| 1873 | March 3 | Act of Congress | 17 Stat. 626 | Crow | ||

| 1873 | April 8 | Executive Order | N/A | 576 | Paiute, et al. | |

| 1873 | April 8 | Executive Order | N/A | 583 | Round Valley Indian Reservation | |

| 1873 | May 2 | Agreement | Amended Agreement with Certain Sioux Indians | 17 Stat. 456; 18 Stat. 167 | Sisseton and Wahpeton Bands of Sioux | |

| 1873 | May 29 | Executive Order | N/A | 643, 644 | Mescalero Apache | |

| 1873 | June 16 | Executive Order | N/A | 545 | Nez Perce | |

| 1873 | July 5 | Executive Order | N/A | 565, 574 | Blackfoot, Gros Ventre, et al. | |

| 1873 | August 5 | Executive Order | N/A | 546 | Apache | |

| 1873 | August 16 | Agreement | N/A | 557 | Crow | |

| 1873 | September 6 | Executive Order | N/A | 405 | Niskwali, et al. | |

| 1873 | September 9 | Executive Order | N/A | 349 | Dwamish, et al. | |

| 1873 | September 13 | Agreement | Brunot Treaty[20] | N/A | 566 | Colorado Ute |

| 1873 | October 3 | Executive Order | N/A | 547, 607 | Tule river, King's river, Owen's river, et al. | |

| 1873 | October 21 | Executive Order | N/A | 548 | Makah | |

| 1873 | November 4 | Executive Order | N/A | 549 | Mississippi Chippewa | |

| 1873 | November 4 | Executive Order | N/A | 550 | Mississippi Chippewa | |

| 1873 | November 4 | Executive Order | N/A | 372, 551 | Quinaielt, Quillehute, et al. | |

| 1873 | November 8 | Executive Order | N/A | 552, 553 | Coeur d'Alene, et al. | |

| 1873 | November 22 | Executive Order | N/A | 554 | Colorado River Indian Reservation | |

| 1873 | November 22 | Executive Order | N/A | 555 | Dwamish, et al. | |

| 1873 | December 10 | Executive Order | N/A | 563 | Jicarilla Apache | |

| 1873 | December 23 | Executive Order | N/A | 351 | Dwamish, et al. | |

| 1873 | December 31 | Executive Order | N/A | Santee Sioux | ||

| 1874 | January 31 | Executive Order | N/A | 557 | Crow | |

| 1874 | February 2 | Executive Order | N/A | 643 | Mescalero Apache | |

| 1874 | February 12 | Executive Order | N/A | 558, 576 | Paiute, et al. | |

| 1874 | February 14 | Executive Order | N/A | Odawa and Ojibwe in Michigan | ||

| 1874 | February 25 | Executive Order | N/A | 559 | Skokomish (S'klallam) | |

| 1874 | March 19 | Executive Order | N/A | 560 | Paiute | |

| 1874 | March 23 | Executive Order | N/A | 561, 562 | Paiute | |

| 1874 | March 25 | Executive Order | N/A | 563 | Apache (Jicarilla bands) | |

| 1874 | April 9 | Executive Order | N/A | 564 | Muckleshoot Indian Reservation | |

| 1874 | April 9 | Executive Order | N/A | 588 | Apache | |

| 1874 | April 15 | Act of Congress | 18 Stat. 28 | 565 | Gros Ventre, Piegan, Blood, Blackfoot, River Crow | |

| 1874 | April 29 | Act of Congress | 18 Stat. 36 | 566 | Ute | |

| 1874 | May 26 | Executive Order | N/A | 567, 568 | Pillager Chippewa | |

| 1874 | June 22 | Act of Congress | 18 Stat. 140 | 569 | L'Anse and Lac Vieux Desert Ojibwe | |

| 1874 | June 22 | Act of Congress | 18 Stat. 166 | 539 | Shoshoni | |

| 1874 | June 22 | Act of Congress | 18 Stat. 167 | 538 | Sisseton and Wahpeton Sioux | |

| 1874 | June 22 | Act of Congress | 18 Stat. 170 | 570 | Omaha | |

| 1874 | June 22 | Act of Congress | N/A | Kickapoo of Texas and Mexico | ||

| 1874 | June 23 | Agreement | N/A | 571 | Eastern Shawnee | |

| 1874 | June 23 | Act of Congress | 18 Stat. 272 | Kaw | ||

| 1874 | June 23 | Act of Congress | 18 Stat. 273 | 572 | Papago | |

| 1874 | June 23 | Act of Congress | 18 Stat. 273 | New York Indians | ||

| 1874 | July 21 | Executive Order | N/A | 573 | Apache | |

| 1874 | August 19 | Executive Order | N/A | 574 | Gros Ventre, Piegan, Blood, Blackfoot, River Crow | |

| 1874 | November 16 | Executive Order | N/A | 466, 554, 593 | ||

| 1874 | November 24 | Executive Order | N/A | 531 | Southern Apache | |

| 1874 | December 15 | Act of Congress | 18 Stat. 291 | 539 | Shoshoni | |

| 1875 | January 11 | Executive Order | N/A | 614 | Sioux | |

| 1875 | February 12 | Executive Order | N/A | 575 | Shoshone, Bannock, Sheepeater | |

| 1875 | March 3 | Act of Congress | 18 Stat. 445 | 576, 577 | Paiute | |

| 1875 | March 3 | Act of Congress | 18 Stat. 446 | 578, 579 | Alsea Indian Reservation, Siletz Indian Reservation | |

| 1875 | March 3 | Act of Congress | 18 Stat. 447 | 580 | Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians | |

| 1875 | March 3 | Act of Congress | 18 Stat. 447 | 571 | Modoc | |

| 1875 | March 16 | Executive Order | N/A | 581 | Sioux | |

| 1875 | March 25 | Executive Order | N/A | 557 | Crow (Judith Basin Indian Reservation) | |

| 1875 | April 13 | Executive Order | N/A | 622, 623 | Gros Ventre, Piegan, Blood, Blackfoot, River Crow | |

| 1875 | April 23 | Executive Order | N/A | 582 | Apache | |

| 1875 | May 15 | Executive Order | N/A | 589, 646 | Paiute and Shoshoni | |

| 1875 | May 18 | Executive Order | N/A | 583 | Round Valley Indian Reservation | |

| 1875 | May 20 | Executive Order | N/A | 614 | Sioux | |

| 1875 | June 10 | Executive Order | N/A | 545 | Nez Perce | |

| 1875 | June 23 | Executive Order | N/A | 584 | Sioux | |

| 1875 | July 3 | Executive Order | N/A | 577 | Paiute | |

| 1875 | October 20 | Executive Order | N/A | Mescalero Apache | ||

| 1875 | October 20 | Executive Order | N/A | 585 | Crow | |

| 1875 | November 22 | Executive Order | N/A | 586 | Ute | |

| 1875 | December 21 | Executive Order | N/A | 587, 588 | Southern Apache | |

| 1875 | December 27 | Executive Order | N/A | Missin Indians (Portrero [Rincon, Gapich, LaJolla], Cahuila, Capitan Grande, Santa Ysabel [Mesa Grande], Pala, Agua Caliente, Sycuan, Inaja, Cosmit) |

1880–present

| ) |

| Year | Date | Treaty Name | Alternative Treaty Name | Statutes | Land Cession Reference (Royce Area) | Tribe(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | January 6 | Executive Order | N/A | 615 | Navajo | |

| 1880 | January 17 | Executive Order | N/A | Mission Indians (Agua Caliente Indian Reservation, Santa Ysabel Indian Reservation) | ||

| 1880 | March 6 | Agreement | 21 Stat. 199 | 616, 617 | Ute | |

| 1880 | March 6 | Executive Order | N/A | 618 | Nez Perce (Moses' Band) | |

| 1880 | March 16 | Act of Congress | 21 Stat. 68 | Kaw | ||

| 1880 | May 14 | Agreement | N/A | Crow | ||

| 1880 | May 14 | Agreement | N/A | Shoshoni, Bannock, and Sheep-eater | ||

| 1880 | June 8 | Executive Order | N/A | Havasupai | ||

| 1880 | June 12 | Agreement | Agreement with the Crows | N/A | 619 | Crow |

| 1880 | June 15 | Act of Congress | N/A | Ute | ||

| 1880 | July 13 | Executive Order | N/A | 620, 621 | Arikara, Gros Ventre, and Mandan | |

| 1880 | July 13 | Executive Order | N/A | 622, 623 | Gros Ventre, Piegan, Blood, Blackfoot, and River Crow | |

| 1880 | July 13 | Executive Order | N/A | 613 | Sioux (Drifting Goose's Band) | |

| 1880 | July 23 | Executive Order | N/A | Malheur Indian Reservation | ||

| 1880 | September 11 | Agreement | N/A | 616, 617 | Ute | |

| 1880 | September 21 | Executive Order | N/A | 624 | Jicarilla Apache | |

| 1880 | November 23 | Executive Order | N/A | Havasupai | ||

| 1882–83 | Agreement with the Sioux of Various Tribes | |||||

| 1883 | Agreement with the Columbia and Colville | |||||

| 1891 | January 12 | Act of Congress | 26 Stat. 712 | Mission Indians | ||

| 1891 | February 13 | Act of Congress | 26 Stat. 749 | Sac and Fox | ||

| 1891 | March 3 | Act of Congress | 26 Stat. 1016 | 506 | Citizen Band of Potawatomi | |

| 1891 | March 3 | Act of Congress | 26 Stat. 1022 | 525 | Cheyenne and Arapaho | |

| 1891 | March 3 | Act of Congress | 26 Stat. 1027 | 553 | Coeur d'Alene | |

| 1891 | March 3 | Act of Congress | 26 Stat. 1032 | 712, 713 | Gros Ventre and Mandan | |

| 1891 | March 3 | Act of Congress | 26 Stat. 1035 | 496 | Sisseton and Wahpeton Sioux | |

| 1891 | March 13 | Act of Congress | 26 Stat. 1016 | 506 | Absentee Shawnee | |

| 1891 | October 16 | Executive Order | N/A | 400, 461 | Hupa et al. | |

| 1892 | June 17 | Executive Order | N/A | 716 | Fort Berthold Indian Reservation | |

| 1892 | June 17 | Act of Congress | 27 Stat. 52 | 400 | Klamath River Indian Reservation | |

| 1892 | July 1 | Act of Congress | 27 Stat. 62 | 717, 718 | Colville Indian Reservation | |

| 1892 | July 13 | Act of Congress | 27 Stat. 124 | 552 | Coeur d'Alene | |

| 1892 | July 13 | Act of Congress | 27 Stat. 139 | 625 | Spokane | |

| 1892 | October 22 | McCumber Agreement | Agreement Between the Turtle Mountain Indians and the Commission | 52nd-2nd-Ex.Doc.229 | Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa | |

| 1892 | November 21 | Executive Order | N/A | 655 | Navajo | |

| 1892 | November 21 | Executive Order | N/A | 719 | Red Lake Band of Chippewa | |

| 1892 | November 28 | Executive Order | N/A | Yakima | ||

| 1893 | February 20 | Act of Congress | 27 Stat. 469 | 720 | White Mountain Apache | |

| 1893 | March 3 | Act of Congress | 27 Stat. 557 | 650 | Kickapoo | |

| 1893 | March 3 | Act of Congress | 27 Stat. 640 | 289 | Cherokee | |

| 1893 | March 3 | Act of Congress | 27 Stat. 643 | 606 | Tonkawa | |

| 1893 | March 3 | Act of Congress | 27 Stat. 644 | 591 | Pawnee | |

| 1893 | April 12 | Executive Order | N/A | Osette Indians | ||

| 1893 | September 11 | Executive Order | N/A | Hoh River Indians | ||

| 1894 | June 6 | Act of Congress | 28 Stat. 86 | 370 | Warm Springs | |

| 1894 | August 15 | Act of Congress | 28 Stat. 314 | 411 | Yankton Sioux | |

| 1894 | August 15 | Act of Congress | 28 Stat. 320 | 400 | Yakima | |

| 1894 | August 15 | Act of Congress | 28 Stat. 332 | 552 | Coeur d'Alene | |

| 1894 | August 15 | Act of Congress | 28 Stat. 320 | Yakima | ||

| 1894 | August 15 | Act of Congress | 28 Stat. 323 | 479 | Alsea et al. | |

| 1894 | August 15 | Act of Congress | 28 Stat. 326 | 442 | Nez Perce | |

| 1894 | August 15 | Act of Congress | 28 Stat. 332 | 652 | Yuma | |