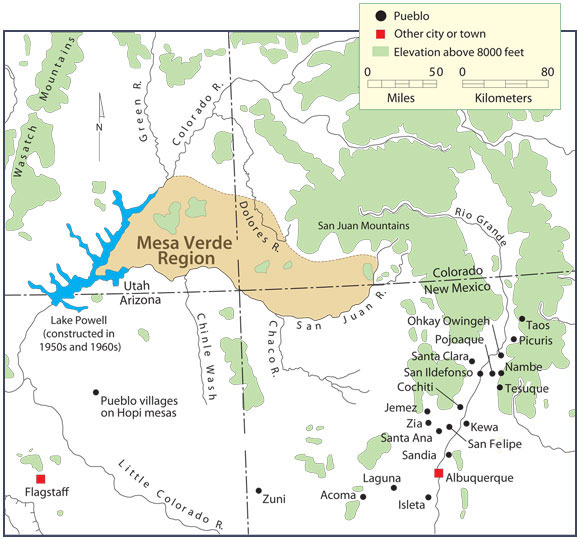

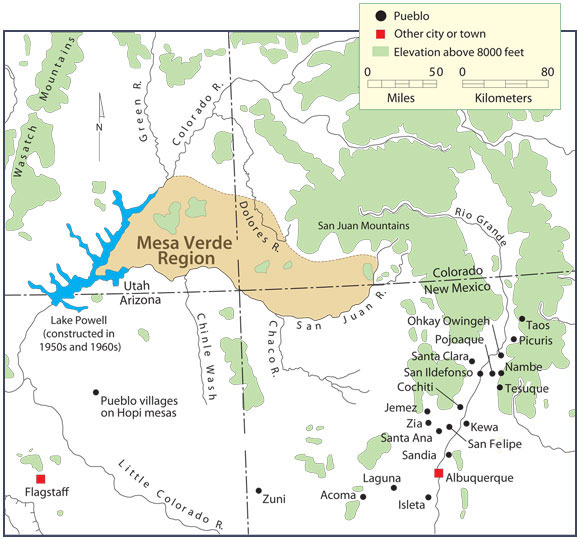

In the American Southwest, the Pueblos of New Mexico and Arizona occupy a unique position. They are in some ways ageless. The Pueblos descend from the time before Europeans, possibly before many of the other tribes of New Mexico and Arizona. The most revealing of ancient pueblo sites have been set aside as Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado's rugged southwest corner, at the Chaco Canyon National Historical Park in the northwest desert of New Mexico, and the Pecos Pueblo National Historical Park in northeastern New Mexico at the edge of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains.

Each of these amazing Parks has been a revelation for ethnologists and archaeologists since the late 19th Century. Today's Pueblos are situated along the Rio Grande River in New Mexico and the Hopi Tribe of Northeastern Arizona. are the descendants of the people who occupied the numerous archaeological sites so many centuries ago. Maize and beans were the plants raised for food, and probably came northward from Mexico long before the Spanish colonial conquest. There were no horses to draw plows. Plowing was done with whatever worked the best in each location. Pueblo religious practices were and are complex and due to hundreds of years of Roman Catholic suppression, any priest is denied the innermost beliefs of Pueblo Culture. Clothes were functional in nature, and women were the leaders in some locations, and men in others. Pueblo life was challenging, and at times the men of different Pueblos would hunt for venison, elk, and trade for bison hides and meat with the Southern Plains Tribes.

The pueblo people were agrarian, raising squash, corn, beans and other vegetables. Fruit was not as prevalent. Pueblo hunters brought home deer, wapiti, buffalo, and smaller game. Many of the pueblos had to eat insects when water was not readily available or there was a severe drought. The famous locations that have been preserved as National Parks and Monuments, such as Mesa Verde, Chaco Culture, Pecos Historical Park, and too many national monuments to name in this article, are available to help visitors to the Southwestern USA to comprehend the complex cultures that occupied the lands in the states of Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, and Colorado. Trade between regions was evident in archaeological digs revealing shells from the California coast, plants domesticated for agriculture by what is now tribes that were in Mexico, and clothing from the Mound Builders of the Midwest.

The remarkable buildings and physical locations of ancient pueblo cultures exemplify the resilience and doggedness that the indigenous people composing the various pueblo cultures in surviving during plentiful years and meager years of food availability. Pottery from the pueblos was present as early as 100 AD. The ingenuity of the pots and other pieces of Anazazi (pre-Columbian) pottery show the practical side of ancient pueblo culture. To cover the various styles of different eras of Anazazi pottery is beyond the scope of this article. The interested reader will find numerous books and articles covering the subject.

The idea of Pueblo pottery being art was a late 19th and early 20th Century shift in the manner in which scholars and pottery aficionados viewed art. The Rio Grande Pueblos and Hopi tribe in Arizona had moved from their mountain homes into the valleys that provided a constant flow of water for the crops they needed to grow. The primary location was in what is now the Rio Grande and Pecos Rivers in New Mexico, and the Little Colorado and Colorado Rivers in Arizona. The more reliable pueblo locations facilitated more time for artistic expression.

PUEBLO AND SURROUNDING CULTURES 1500 AD

PUEBLOS OF THE RIO GRANDE AND HOPI PUEBLOS 1750 AD

PUEBLO CULTURE WITH SURROUNDING TRIBES 2015

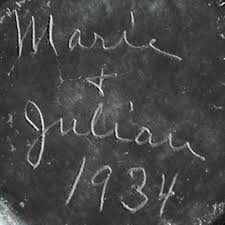

1934

Each of these amazing Parks has been a revelation for ethnologists and archaeologists since the late 19th Century. Today's Pueblos are situated along the Rio Grande River in New Mexico and the Hopi Tribe of Northeastern Arizona. are the descendants of the people who occupied the numerous archaeological sites so many centuries ago. Maize and beans were the plants raised for food, and probably came northward from Mexico long before the Spanish colonial conquest. There were no horses to draw plows. Plowing was done with whatever worked the best in each location. Pueblo religious practices were and are complex and due to hundreds of years of Roman Catholic suppression, any priest is denied the innermost beliefs of Pueblo Culture. Clothes were functional in nature, and women were the leaders in some locations, and men in others. Pueblo life was challenging, and at times the men of different Pueblos would hunt for venison, elk, and trade for bison hides and meat with the Southern Plains Tribes.

The pueblo people were agrarian, raising squash, corn, beans and other vegetables. Fruit was not as prevalent. Pueblo hunters brought home deer, wapiti, buffalo, and smaller game. Many of the pueblos had to eat insects when water was not readily available or there was a severe drought. The famous locations that have been preserved as National Parks and Monuments, such as Mesa Verde, Chaco Culture, Pecos Historical Park, and too many national monuments to name in this article, are available to help visitors to the Southwestern USA to comprehend the complex cultures that occupied the lands in the states of Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, and Colorado. Trade between regions was evident in archaeological digs revealing shells from the California coast, plants domesticated for agriculture by what is now tribes that were in Mexico, and clothing from the Mound Builders of the Midwest.

The remarkable buildings and physical locations of ancient pueblo cultures exemplify the resilience and doggedness that the indigenous people composing the various pueblo cultures in surviving during plentiful years and meager years of food availability. Pottery from the pueblos was present as early as 100 AD. The ingenuity of the pots and other pieces of Anazazi (pre-Columbian) pottery show the practical side of ancient pueblo culture. To cover the various styles of different eras of Anazazi pottery is beyond the scope of this article. The interested reader will find numerous books and articles covering the subject.

The idea of Pueblo pottery being art was a late 19th and early 20th Century shift in the manner in which scholars and pottery aficionados viewed art. The Rio Grande Pueblos and Hopi tribe in Arizona had moved from their mountain homes into the valleys that provided a constant flow of water for the crops they needed to grow. The primary location was in what is now the Rio Grande and Pecos Rivers in New Mexico, and the Little Colorado and Colorado Rivers in Arizona. The more reliable pueblo locations facilitated more time for artistic expression.

MAP OF PRE-COLUMBIAN CULTURES OF THE SOUTHWEST 1000 AD

PUEBLO AND SURROUNDING CULTURES 1500 AD

PUEBLOS OF THE RIO GRANDE AND HOPI PUEBLOS 1750 AD

PUEBLO CULTURE WITH SURROUNDING TRIBES 2015

As may be viewed from following the progression of Pueblo Culture from Pre-Columbian times through the present day, Pueblo Culture location change inevitably moved the Anazazi from intermittent water sources into the Rio Grande Valley. The migration enabled Pueblos to maintain their locations through all of the various powers that have politically occupied the area. These include Spanish, Mexican, and American governments. The Pueblos face new challenges at this time, such as keeping their water rights, keeping their land from being usurped, and ongoing interference with their indigenous culture.

The revival of the ancient art of making pottery was a necessary and important tool for surviving the years of drought, storing grains for freshness, and use when consuming food. In his beautiful book entitled Maria, published by Northland Press of Flagstaff, Arizona in 1979, author Richard Spivey carefully charts the development of the most renowned of Pueblo potters, Maria Montoya Poveka Martinez. From the turn of the 19th Century into the 20th Century, until her death in 1980, Maria Martinez and her husband Julian Martinez, son-Popovi Da, and grandson-Tony Da, pursued their pot painting craft in a manner that made Maria's pottery unique and innovative at a time in the late 19th Century and the first decade of the 20th Century when the artisanship of pottery was dying due to the convienence of cheap and mass produced pottery that even the Pueblos used instead of throwing pottery themselves in the ancient way.

By 1904, Maria and Julian had become famous enough to be asked to exhibit their work at the St. Louis World's Fair of 1904. The indigenous people attending that fair were supposed to dance. Maria used the opportunity to throw pottery, exhibiting her growing mastery of the ancient art. According to Richard Spivey, Maria also attended the 1914 San Diego World's Fair, the 1934 World's Fair in Chicago, and the 1939 World's Fair in San Francisco, the last one she attended. To give an idea of the prestige she held in the art world, Maria was awarded a gold medal by the University of Colorado in 1953. She was awarded The Craftsmanship Medal of the American Institute of Architects in 1954, the Palmes Academiques by the Nation of France, also in 1954, and the Jane Addams Award for Distinguished Service by Rockford College in 1959. The American Ceramic Society presented its Presidential Citation in 1967. She was presented the Symbol of Man Award by the Minnesota Museum of Fine Arts in 1969, the Honorary Doctorate in Fine Arts by New Mexico State University was awarded to Maria Martinez. Awards were given by the State of New Mexico, including an award from Governor Bruce King for being an outstanding representative of New Mexico to the world.

Maria, Potter of San Ildefonso - 26 minutes

Hands of Maria Part 1-7 minutes

Hands of Maria Part 2 - 7 minutes

Colores: Pottery of Maria

and Julian Martinez - 8 minutes

Native American Pottery Making Circa

1920-1949 - 5 minutes

1920-1949 - 5 minutes

Maria Martinez Gathering Clay - 3 minutes

The Pottery of Maria Martinez - 7 minutes

Maria Martinez: Identifying Pottery by

Maria That is Black

Maria That is Black

or Red

4 minutes

Pueblo and Maria Martinez Pottery:

What to look for in What Condition

Marvin Martinez (Maria's Great Grandson) talks

about The Martinez Family - 7 minutes

Pot completed by Maria and Julian just prior to Julian Marinez's Death in 1940

Maria and Julian were the first innovators of Indigenous Pottery, and what followed was a major renaissance in the art throughout the various Pueblos. San Ildefonso's neighboring pueblo, Santa Clara Pueblo has produced some exceptional indigenous potters who have received great acclaim.

Maria and Julian Signature at bottom of pot they made

1940

Maria and Julian's Signature at the bottom of pot they made

Upon the passing of Julian Martinez in 1943 at the relatively young age of 46, Maria Martinez faced the challenge of finding another painter of her pottery. She did not have to look very far, as her son Popovi Da was able to fill the large function that Maria's husband previously provided. Popovi brought a new form of painting to Maria's pottery, and excelled in his chosen vocation as much as Julian had previously.

Examples of Black on Black Pottery by Maria and Julian

Martinez

Popovi Da brought a significant innovation to the art of painting Maria's pottery. While keeping Julian Martinez's symbols, many of which derived from Pre-Columbian Times. Popovi Da expanded the types of Pueblo symbols shown on Maria's pottery. He expanded the colors used for decoration as well. Maria also worked with Santana, a relative of hers who has become a highly respected potter and has continued the innovations begun with Maria and Julian. Popovi became the person who fired Maria's pottery, with her participation. Popovi Da died in

Puebloan: Maria Martinez, Black-on-black ceramic vessel by Dr. Suzanne Newman Fricke - UNIVERSITY OF NEW MEXICO

"Born Maria Antonia Montoya, Maria Martinez became one of the best-known Native potters of the twentieth century due to her excellence as a ceramist and her connections with a larger, predominantly non-Native audience. Though she lived at the Pueblo of San Ildefonso, about 20 miles north of Santa Fe, New Mexico, from her birth in 1887 until her death in 1980, her work and her life had a wide reaching importance to the Native art world by reframing Native ceramics as a fine art. Before the arrival of the railroad to the area in the 1880s, pots were used in the Pueblos for food storage, cooking, and ceremonies. But with inexpensive pots appearing along the rail line, these practices were in decline. By the 1910s, Ms. Martinez found a way to continue the art by selling her pots to a non-Native audience where they were purchased as something beautiful to look at rather than as utilitarian objects."

Maria Martinez shown with physicist Enrico Fermi, c. 1948 (public domain; photo by U.S. Government employee made for U.S. Government)

"Making ceramics in the Pueblo was considered a communal activity, where different steps in the process were often shared. The potters helped each other with the arduous tasks such as mixing the paints and polishing the slip. Ms. Martinez would form the perfectly symmetrical vessels by hand and leave the decorating to others. Throughout her career, she worked with different family members, including her husband Julian, her son Adam and his wife Santana, and her son Popovi Da. As the pots moved into a fine art market, Ms. Martinez was encouraged to sign her name on the bottom of her pots. Though this denied the communal nature of the art, she began to do so as it resulted in more money per pot. To help other potters in the Pueblo, Ms. Martinez was known to have signed the pots of others, lending her name to help the community. Helping her Pueblo was of paramount importance to Ms. Martinez. She lived as a normal Pueblo woman, avoiding self-promotion and insisting to scholars that she was just a wife and mother even as her reputation in the world burgeoned."

Maria Martinez, Black-on-black ceramic vessel, c. 1939, blackware ceramic, 11 1/8 x 13 inches, Tewa, Puebloan, San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico (National Museum of Women in the Arts)

Maria Martinez made this jar by mixing clay with volcanic ash found on her pueblo and building up the basic form with coils of clay that she scraped and smoothed with a gourd tool. Once the jar had dried and hardened, she polished its surface with a small stone. Her husband Julian then painted on the design with liquid clay, producing a matte surface that contrasts with the high polished areas. During the firing process, the oxygen supply was cut off, producing carbon smoke that turned the jar black.

Martinez’s works exemplify a collaborative approach to art. She learned how to make pottery from female family members, worked alongside her sisters (who often painted designs on her earliest pieces of pottery), and subsequently trained three generations of her family in the art form. Martinez and her husband, painter Julian Martinez, developed their distinctive black-on-black designs around 1918. Julian rendered birds and serpents or stylized geometric forms that complement the robust forms of his wife’s pottery. Despite achieving great pro

"Maria Martinez eschewed the Western notion of the isolated artistic genius, stating: “I just thank God because [my work is] not only for me; it’s for all the people. I said to my God, the Great Spirit, Mother Earth gave me this luck. So I’m not going to keep it." (Commentary by Maria Martinez, Courtesy National Museum of Women in the Arts)

"Maria and Julian Martinez pioneered a style of applying a matte-black design over polished-black. Similar to the pot pictured here, the design was based on pottery sherds found on an Ancestral Pueblo dig site dating to the twelfth to seventeenth centuries at what is now known as Bandelier National Monument. The Martinezes worked at the site, with Julian helping the archaeologists at the dig and Maria helping at the campsite. Julian Martinez spent time drawing and painting the designs found on the walls and on the sherds of pottery into his notebooks, designs he later recreated on pots. In the 1910s, Maria and Julian worked together to recreate the black-on-black ware they found at the dig, experimenting with clay from different areas and using different firing techniques. Taking a cue from Santa Clara pots, they discovered that smothering the fire with powdered manure removed the oxygen while retaining the heat and resulted in a pot that was blackened. This resulted in a pot that was less hard and not entirely watertight, which worked for the new market that prized decorative use over utilitarian value. The areas that were burnished had a shiny black surface and the areas painted with guaco were matte designs based on natural phenomenon, such as rain clouds, bird feathers, rows of planted corn, and the flow of rivers."

"The olla pictured above features two design bands, one across the widest part of the pot and the other around the neck. The elements inside are abstract but suggest a bird in flight with rain clouds above, perhaps a prayer for rain that could be flown up to the sky. These designs are exaggerated due to the low rounded shapes of the pot, which are bulbous around the shoulder then narrow at the top. The shape, color, and designs fit the contemporary Art Deco movement, which was popular between the two World Wars and emphasized bold, geometric forms and colors. With its dramatic shape and the high polish of surface, this pot exemplifies Maria Martinez’s skill in transforming a utilitarian object into a fine art.The work of Maria Martinez marks an important point in the long history of Pueblo pottery. Ceramics from the Southwest trace a connection from the Ancestral Pueblo to the modern Pueblo eras. Given the absence of written records, tracing the changes in the shapes, materials, and designs on the long-lasting sherds found across the area allow scholars to see connections and innovations. Maria Martinez brought the distinctive Pueblo style into a wider context, allowing Native and non-Native audiences to appreciate the art form."

Links: